A Time in History: New Wave Distilling

I grew up with a firm view of what a whisky distillery should look like. My mother came from the village of Bunnahabhain on Islay and her family worked in its distillery from the first mash in 1883. The complex of large, whitewashed buildings, facing the sea and crowned with pagodas, remains for me the epitome of Scotch whisky.

There was certainly no visitor centre and the military discipline with which the whole village was run would not have encouraged one. The same was true throughout Scotland’s whisky regions until quite recently. They were places of craft and production; the secrets of brands and blends jealously guarded within their walls.

Most of Scotland’s distilleries were built in the 19th century, but now a strong whiff of modernity is in the air. In 2009, there were 96 licensed distilleries. Today, there are 118. The Scotch Whisky Association provided a list of 40 distillery projects at various stages of development. Some will fall by the wayside but their shared ambition is to produce a distinctive whisky which will secure a place in the single malt market.

This is a significantly different model to the one which has characterised the industry for generations. These new distilleries are apart from the blended whisky market into which the vast majority of current production still flows. They are small-volume projects, likely to employ more people in visitor centres than in the actual production of whisky.

On that basis, they are emerging as assets to the industry by adding diversity, and to many local communities which were previously non-participants in Scotland’s whisky trail. At some point, the bigger players may become irritated by a profusion of newly-emergent labels on the shelves. In reality however, the vast majority will remain as niche players, creating their own markets while offering distinctive nuances of place and process.

The biggest challenge facing entrepreneurs behind these 40 projects is how to bridge the financial gap which the whisky-making process dictates. Once the distillery is up and running, there will be a minimum of three years before anything it produces can be sold as Scotch Whisky. So how do they keep the wheels turning in the meantime?

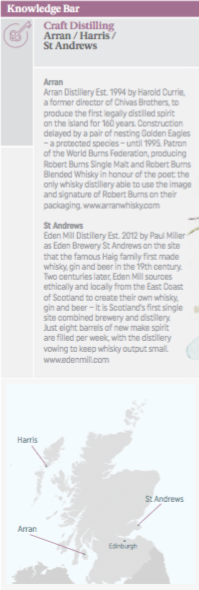

I became aware of this problem through the experience of Arran distillery. My Parliamentary constituency included Arran and I was a supporter of plans to build a distillery at Lochranza, in the north-west of the island. (Incredibly,Scottish Natural Heritage objected on grounds of ‘visual intrusion’ but we managed to see that off). Arran is one of Scotland’s major tourist destinations and this can now be seen as first of the ‘new-wave’ distilleries, opened in 1994.

Arran has become a success story and, indeed, the current owners have obtained planning consent for a second distillery at Lagg, in the south of the island. But I remember the challenges which the originators of the project faced in bridging that ‘three year gap’, which eventually led to them ceding control in order for the business to survive. It is a warning story I have told to a few would-be whisky magnates.

One effective solution seems to have emerged in the meantime and it is called… ‘gin’. While it takes three years to produce whisky, gin can be turned around in no time at all. What’s more, the production process lends itself to endless ingredient options, each with the potential to add local character both to the flavour and the marketing.

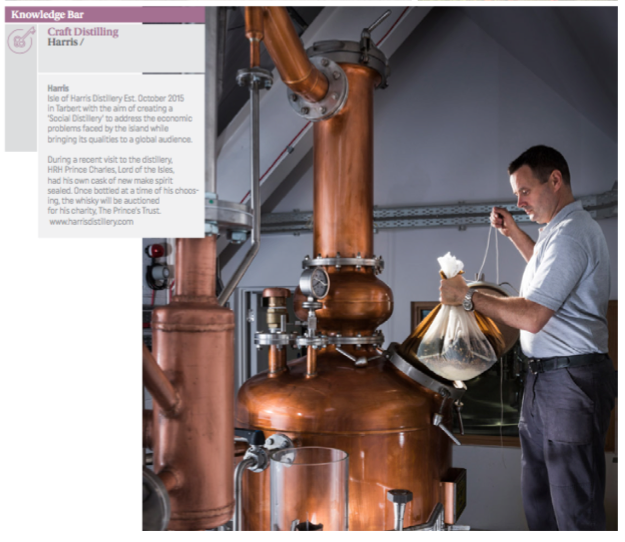

One outstanding example of this strategy lies in the Isle of Harris distillery in the Outer Hebrides. Located close to the ferry terminal at Tarbert, this is the brainchild of Anderson “Burr” Bakewell, an American-born musicologist who has had a 50-year love affair with Harris. Anxious to help its fragile economy, he decided there was “no better way to share the place than to put it in a bottle”.

Every aspect of Harris Distillery has been delivered to impeccable standards and it is already a huge tourist attraction, with 60,000 visitors in its first year. For the time being, most of them take away a bottle of Isle of Harris Gin. It is infused with seven botanicals including sugar kelp collected from local shores to suggest just a hint of the sea. Beautiful packaging and skilful marketing have helped make Harris Gin a sought-after product in its own right.

The first whisky should be ready later this year but nothing will be hurried. Burr says: “I’m told we have ideal maritime conditions for maturation. Conditions are so different from the mainland and even Islay is exposed to different forces. We have the softest water in Scotland and atmospheric pressure which is very different even from the Inner Isles”. In short, he adds: “Some distilleries struggle with defining themselves and differentiating. We don’t have that problem”.

It took several years to raise funding, and Harris Distillery now has 18 investors. “The meetings with people looking for short-term returns were very brief,” recalls Burr. “We have individuals who wanted to hand something down to their children or grand-children. They know that most distilleries were built in Victorian times, so this is a business that lasts. That is what appealed to them and most have become very interested in each stage of progress”.

With an annual output of just 100,000 litres, Harris Whisky will take scarcely a sip out of the Scotch Whisky market. But the love and enthusiasm which clearly goes into it is likely to translate into a loyal body of followers who, like Burr, will find a highly distinctive taste of Harris in every glass. For good measure, the project has given a real boost to a fragile island economy, already providing more than 30 jobs. What is there not to like?

There is a similar story on the other side of Scotland at Guardbridge in Fife where a closed-down paper mill houses the Eden Mill brewery and distillery. The founder, Paul Miller, says that new distilleries, because they are small, can “add a further layer of crafting to an iconic product”. He quotes two examples of how they are applying this principle – innovating with different barleys, normally reserved for brewing, in the malting process and using high quality ‘first fill barrels’, fresh from their original sherry or bourbon purpose, for maturation.

Paul believes that the Scotch Whisky industry and image need this kind of innovation and diversity to stay ahead of the global game. Craft distilling is becoming popular in other countries too, he points out. He also thinks that the small distilleries can “educate and explain” to a wider audience by improving on the “formulaic” visitor centre experience. Eden Mill is currently listed as the number one visitor attraction in Fife by TripAdvisor.

Like Harris, Eden Mill has become well-known among a discerning audience for its gin before the whisky comes on-stream in November. There was no master-plan, says Paul, and their original model was based on brewing beer while the whisky side of the business developed. But developing gins matched the skill set for their distilling staff and the market responded positively. As a result, the Eden Mill brand will be much better known even before the whisky appears.

The Scotch Whisky Association welcomes the investment coming into the industry through small new ventures while, at the same time, the big players invest in expanding capacity. The SWA do not see quality control as an issue because that is dealt with through Westminster legislation which defines and protects the product, most recently the Scotch Whisky Regulations of 2010.

With more Scottish communities involved in whisky production and more craft products for whisky aficionados to sample, it all seems like a story worthy of a toast – even if these new-look distilleries-cum-visitor centres don’t quite match my Bunnahabhain visual ideal.

4.7/5 with 10,000+ reviews

4.7/5 with 10,000+ reviews