Treasure Island: The Isle of Raasay

"Distillery plans revealed for tiny Hebridean island," ran the headline in 2015 to intimate the Isle of Raasay's whisky-producing future. The writer had fallen for a cliché since Raasay is scarcely "tiny." Fourteen miles long, its landmass is greater than Manhattan's.

Raasay is separated from Skye by a 25-minute ferry crossing and maintains its own very distinct identity. The population can be fairly described as "tiny" - currently 160, and one in eight works for the distillery which released its first edition late last year - a Tennessee barrel matured, lightly peated spirit finished in red wine casks.

That makes the Isle of Raasay Distillery a success story which the island has long been seeking. Even by Highland and Islands standards, Raasay has suffered harshly from the capricious forces of ownership and neglect. It was due an upturn in fortune which the distillery has provided.

It does no harm that the operations director, Norman Gillies, has a Raasay pedigree stretching back centuries. He is committed to ensuring that "everything we send out of Raasay leaves in a bottle," so the more labour intensive links in the chain are retained on the island.

Norman also points out: "A number of our staff are university-educated island natives who moved back to work here. To me, the difference between this and other industries in the island is that there is so much scope to learn and progress."

He himself left Raasay to graduate in civil engineering with no obvious way back. The opportunity arose when he was employed on the groundworks for the new distillery. That led to a career change, with Norman concluding that "whisky is more interesting than cement."

The creation of Raasay's distillery fulfils a shared ambition of two Scottish entrepreneurs, Bill Dobbie and Alasdair Day. Bill's background is in private equity while Alasdair has a whisky lineage in the Scottish Borders. They came together in 2014, originally with the idea of creating a Borders distillery. Soon after, however, the Raasay opportunity presented itself and became the priority.

For a flavour of the forces that shaped present-day Raasay, you have to go back (at least) to the early 1800s. It had been the relatively benign clan fiefdom of the MacLeods of Raasay for centuries, but the chief made the mistake of backing the Jacobites in 1745 and the islanders suffered retribution accordingly.

The good life was soon resumed at the top end of the clan pyramid. When Samuel Johnson and James Boswell famously toured the Hebrides in 1773, they found hospitality of the highest order at Raasay House. "We had a dram of excellent brandy, according to the island custom, filled round. They call it a scalck. On a sideboard was served up directly, for us who had come off the sea, mutton chops and tarts, with porter, claret, mountain and punch. Then we took coffee and tea. In a little, a fiddler appeared and a little ball began."

Alas, the loyal clansfolk fared less well. In due course, the MacLeods - like many chiefs-turned-proprietors - wined and dined their way into bankruptcy. In 1843, the island was sold to George Rainy, son of a Presbyterian minister from Sutherland. The chief accepted 35 thousand guineas and promptly departed for Tasmania. There is to this day a resident of that far-off island who lays claim to the title MacLeod of Raasay, solemnly upheld by the Lord Lyon King of Arms.

Rainy had made his fortune in the Caribbean slave trade and in 1837 was one of the biggest beneficiaries of compensation from the British Government after slavery was abolished. Having bought Raasay and the neighbouring island of Rona, Rainey applied the talent for ruthlessness he had developed on the sugar plantations of Guyana.

Half of Raasay was given over to sheep and 12 villages cleared. Two boatloads of islanders were sent to America; another to Australia. A ban on the reproduction of children was introduced and when one islander transgressed, he was burnt out of his home. These accounts of Rainy's tyranny emerged through evidence to the Napier Commission - set up to investigate conditions in the Highlands and Islands - when it visited Raasay in 1883. One of the witnesses to the Commission, John Gillies, was Norman's great, great grandfather.

Rainy's successor preferred shooting deer to farming sheep, leading to further evictions. In 1911, Raasay's lottery of private ownership took a further curious turn when the island was bought by the industrial behemoth, William Baird and Co., then the world's largest producers of iron ore.

Raasay is mineral rich and Baird's bought it to establish an iron ore mine at the south end of the island. They built rows of cottages - which still form the main settlement of Inverarish - and commissioned a pier and railway. On the outbreak of war most of the local workers went off to fight for King and Country. The war effort needed iron ore and the Munitions Ministry sent German prisoners of war to supplement the labour force. They lived in the cottages and relationships with the islanders were good on a human level. However, Baird's used them to undercut wages and the treatment of Raasay workers became an unlikely national cause celebre.

In 1917, a delegation from the Raasay Miners' and Workers' Union travelled to London to meet Winston Churchill. A truce was patched up and Baird's departed after the war. Demand for land from ex-servicemen forced the government to take over estates, including Raasay, to divide them into crofts. That alone did not address the problem that has persisted ever since - the need for employment to supplement meagre earnings from working inhospitable land.

For such a small community, Raasay has attracted a remarkably rich cast-list of extraordinary characters. One remembered with no fondness is a doctor from Sussex, John Green. By some mysterious process in the early 1960s, Green bought the key properties on the island from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland at a knock-down price. These included Raasay House, neighbouring Borodale House and the Home Farm which provided the island's milk.

It gradually became apparent that he had not the slightest intention of doing anything with these assets other than leave them to rot. The story ran and ran, particularly when Green objected to building a slipway for a car ferry on the grounds that it would spoil the view from Raasay House (which he visited only once). In the 1970s, Raasay and "Dr No" became symbolic of the Highland land ownership debate which was slightly ironic since Green owned only a tiny fraction of the island - though enough to block development and, for years, deprive the islanders of a car ferry. Eventually, the Highlands and Islands Development Board bought him out in 1979.

That left them with the problem - how to create employment on the island? Raasay House was rescued from dereliction to become an outdoor centre while Borodale House was extended to become a hotel. By 2012, it had gone bust and that in turn paved the way for the Isle of Raasay Distillery.

Among the new generation of small craft distilleries, Raasay's stands out as a masterpiece. The extension of Borodale House to accommodate the distilling process is elegantly designed and the views across to the Cuillin of Skye are stunning. On top of all that, there are these precious jobs. There were 10,000 visitors in 2019 before the coronavirus pandemic struck.

Norman Gillies sees it as work in progress. The first release of 7,500 bottles was pre-sold and with their own whisky to market, Norman expects export demand to rise. Along with the University of the Highlands and Islands, they are experimenting with strains of barley - Norwegian and Icelandic look most promising - to create an entirely island whisky. Isle of Raasay Gin has proved a great success: "We initially didn't intend to produce a gin," he says, "but people almost assume that you will - so we did." The next milestone in May will be the launch of their signature Isle of Raasay Single Malt.

It's all good news. If you could bottle Raasay's turbulent history, it too would be a bestseller. More than at any point in the past couple of centuries, the current chapter holds the promise of a better future.

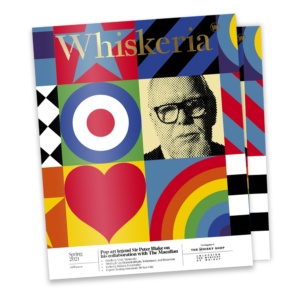

The original feature is from the Spring 2021 edition of Whiskeria, delivered to the door of W Club subscribers and also free with any Whisky Shop purchase in store or online. Click here to read the full Spring 2021 issue of Whiskeria online for free.

4.7/5 with 10,000+ reviews

4.7/5 with 10,000+ reviews