Tobermory Distillery - What's The Story?

The port of Tobermory, on the Hebridean island of Mull, is notable for a seafront filled with houses and shops painted in bold, primary colours. It is also at the centre of a fascinating tale of long-lost gold. Back in 1588, the Spanish Armada had been defeated by the English navy, led by Sir Francis Drake, and those ships that survived made their way home to Spain around the north and west coasts of Scotland.

One vessel – believed to be the San Juan de Sicilia – took refuge in Tobermory Bay, having suffered damage during the battle with the English forces. The 800-tonne ship spent a month in the bay, being repaired and taking on fresh supplies. Then, in early November, she mysteriously blew up, and sank to the sea bed, taking with her, it is claimed, a horde of gold coins worth £30 million today. Several efforts have been made to locate the vessel and liberate its legendary cargo, but all have failed.

Liquid gold

Tobermory is also famous for gold of another kind. Liquid gold. A distillery was established in the port during 1798, crammed into a tight site beside the Ledaig Burn, between a hillside rising above the town and head of the bay. It was constructed by local merchant John Sinclair, a decade after the settlement of Tobermory itself had been founded by the British Fisheries Society.

This body had been set up to stimulate commercial fishing in the Highlands and Islands, and was responsible for the development of Tobermory and Ullapool in 1788, Lochbay on the Isle of Skye in 1790, and Pultneytown at Wick, Caithness during 1808.

John Sinclair applied for permission to build a distillery and several houses on 57 acres of land to the south of the harbour in 1797, but initially the authorities wanted him to set up a brewery instead. Despite this, the merchant stuck to his original plan and somehow had it approved. He named his new distillery Ledaig (pronounced Led-chigg), which translates from Gaelic as ‘safe haven.’

However, during the ensuing two centuries Ledaig was to be far from a safe haven for whisky-making, as the distillery has actually been silent for more than half of its entire existence. It was first closed between 1837 and 1878, but was back in production when journalist and distillery chronicler Alfred Barnard visited in 1885.

Barnard subsequently wrote that “The voyage from Oban to Tobermory in fine weather is one of the pleasantest imaginable; the scenery is described in many of the guidebooks, but none of them have ever done it justice.”

Today, CalMac car ferries still depart the mainland at the West Highland port of Oban, but instead of arriving in Tobermory, they make landfall at Craignure in the south-east of the island, and 20 miles from the capital. However, Barnard’s observations about the attractions of the scenery during the 50-minutes sea crossing are still as valid as ever.

At the time of Barnard’s visit, Tobermory distillery was licenced to Messrs Mackill Brothers, whom he described as “…noted breeders of cattle,” and wrote of the distillery being “…built with stone in the form of a double triangle.”

He went on to write that “We next bent our steps to the Distilling House, and were there shown two ‘Old Pot Stills,’ the Wash Still holding 2,530 gallons [11,502 litres], and the Spirit Still 1,710 gallons [7,774 litres], the former heated by fire and the latter by steam… The make is called ‘Mull Whisky;’ it is pure Highland malt, and the annual output (1885) was 62,000 gallons [282,000 litres].”

[In 2015], the oldest expressions of Tobermory and Ledaig were released, setting the seal on the distillery's reputation as home to truly serious single malt whiskies.

Hard times and revival

Tobermory was just one of many Scottish distilleries to fall victim to the economic slump between the two world wars of the 20th century, and it was silent once more from 1930 until 1972, having been bought by the Distillers Company Ltd in 1916. Prior to its next bout of whisky production, the site served as a canteen for sailors and the warehouse as a repository for naval stores during the Second World War.

1972 saw production recommence, this time under the auspices of the Ledaig Distillery Ltd, which was formed by a Liverpool shipping operator and the Spanish sherry firm of Pedro Domecq, along with unspecified ‘Panamanian interests.’ For two years prior to its re-opening, the distillery had been extensively reconstructed, and capacity more than doubled.

However, Ledaig Distillery Ltd went bankrupt in 1975, leading to a further four years of silence. The Yorkshire-based Kirkleavington Property Company Ltd bought Tobermory in 1979, but they also found profits elusive, committing the cardinal sin of selling the distillery’s only warehouse for re-development into apartments. They then closed the plant between 1982 and 1989, rather improbably using it for the storage of Isle of Mull cheddar cheese.

Writing in his 1985 book Scotch and Water, after visiting the silent Tobermory distillery, Neil Wilson posed the question “How terminal is the distillery’s position? Although the relatively good condition of the plant offers some hope for the future, its poor layout, and the lack of sufficient warehousing, suggests that a large injection of capital – as much as £1.8m – is desperately required… In the present economic climate it is becoming increasingly unlikely that Tobermory will ever produce malt whisky again.”

Happily, for Tobermory, however, Wilson’s pessimism was unfounded. Burn Stewart Distillers, which already owned Deanston in Perthshire, saw potential in the only distillery on Mull, and in 1993 spent £600,000 buying it, devoting a further £200,000 to acquiring a patchy inventory of maturing stock.

One of the East Kilbride-based company’s first tasks was to remove all traces of cheese from the distillery, before setting about making whisky once again. In the past, Tobermory had distilled both unpeated and peated spirit at varying times, so it was decided in 1996 to split annual production approximately 50:50 between the two, with the peated spirit (using malt at 35-40ppm) being named Ledaig.

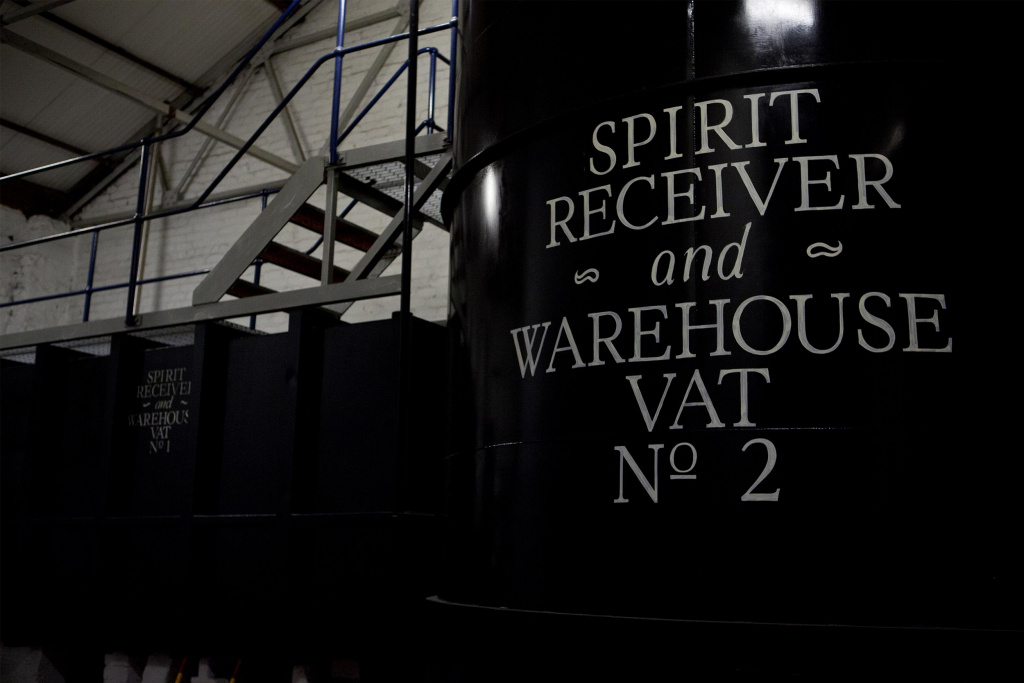

Burn Stewart subsequently devoted significant amounts of time and money to raising the profile of the distillery’s two single malts, and the firm also uses Tobermory and Ledaig in its Scottish Leader and Black Bottle blends. A former tun room was converted into a small warehouse during 2007 so that at least some of the spirit being made can be matured in its place of origin.

In 2002, Burn Stewart had been acquired by Trinidad-based venture capitalists CL Financial for £50 million, but having experienced economic difficulties, CL sold the company to South-African-headquartered The Distell Group for £160 million in 2013.

The whiskies

Two years later, the oldest expressions of Tobermory and Ledaig were released, setting the seal on the distillery’s reputation as home to truly serious single malt whiskies. Both had been aged for 42 years, and comprised some of the first spirit made when production resumed in 1972. The Ledaig carries the name 'Dùsgadh' – Gaelic for 'awakening' – and contains the last of the distillery’s pre-1996 peated spirit.

Today’s core Tobermory line-up comprises a 12-year-old Tobermory, released in 2019 in place of the previous 10-year-old, along with 10 and 18-year-old Ledaigs. 2019 also saw the release of a Tobermory (1999) Marsala Finish and a Ledaig (1997) Manzanilla Finish in Distell’s annual Limited Release Collection, with more such limited expressions – and one or two surprises – expected later this year.

Tobermory is equipped with a five-tonne cast iron traditional mash tun, four Oregon pine washbacks and two pairs of stills, giving the distillery a maximum capacity of one million litres per annum. The site is currently operating at around 75 per cent of that capacity. The four tall stills stand in line, with condensers located high above the vessels, among the roof supports of the stillroom. Tobermory’s spirit style is influenced by slow distillation and by the equipment’s design, with stills boasting ‘boil bulbs’ and ‘S’-shaped lyne arms that increase reflux and ‘lighten’ the spirit character, while giving a slightly oily character with citrus notes.

Looking to the future

Between 2017 and 2019, the distillery was silent once again, but this time in a much more positive way than on previous occasions, while a major renovation programme took place in both the production and visitor centre areas, ‘future-proofing’ the distillery for decades to come.

As Brand Home Manager Olivier MacLean explains, “Since April 2017 we have replaced the following parts in the distillery: all four washbacks, one sprit still and one wash still, a new draff silo and some refurbishment within the distillery. We also put a new roof on the still house as well as on the fermentation area.”

Additionally, a new stillroom has been created, equipped with a gin still, and Tobermory Hebridean Gin, containing locally-sourced botanicals and a quantity of the distillery’s new-make malt spirit, is proving extremely popular with consumers.

Due to the fact that the distillery only has the small maturation area created in 2007, most of the spirit made at Tobermory is aged on the mainland. Olivier MacLean notes that “We only mature a few casks on site which are most likely ex-bourbon. Our spirit is taken by tanker twice a week to Deanston in order to fill it to cask. After maturation at Deanston warehouse, the casks go to our bottling plant at East Kilbride to be bottled.”

Although he boasts a famous Mull surname – the island’s Duart Castle has been the seat of Clan MacLean for over 700 years – Olivier hails from Switzerland and has occupied his present role since last September. “I feel very fortunate to have this role at this unique and special place,” he says. “Our distillery is a jewel on Mull.”

When it comes to his own favourite drams, MacLean declares that “I consider myself a ‘peat head’, so I do prefer a peated, smoky single malt. My personal favourite at the moment is our Ledaig 21 Year Old Port Pipe – a distillery-exclusive bottle.”

Other distillery-exclusive expressions available to reward those making the journey to Tobermory currently include a 20-year-old Ledaig Moscatel Finish, and there is the opportunity to hand-fill your own bottle from the array of single malts on offer.

The chances of the gold in Tobermory Bay being discovered remain remote, but having survived through many uncertain times, the island’s ‘other’ gold is definitely something to be treasured.

“I consider myself a ‘peat head’, so I do prefer a peated, smoky single malt. My personal favourite at the moment is our Ledaig 21 Year Old Port Pipe – a distillery-exclusive bottle.”

Brand Home Manager

Olivier MacLean

This article appeared in the Summer 2020 edition of Whiskeria. Pick up a copy in-store or join The W Club to have each new issue delivered directly to your door.

4.7/5 with 10,000+ reviews

4.7/5 with 10,000+ reviews